What to expect from Donald Trump’s Stormy Daniels trial

There’s a poetic irony that the presiding judge in Donald Trump’s so-called Stormy Daniels criminal trial is an immigrant from what Trump might refer to as a “shithole country.” Judge Juan Merchan was born in Bogotá, Colombia. He immigrated to New York City with his parents when he was six years old. Fortunately Stephen Miller wasn’t around back then to advise President Lyndon Johnson to separate him from his parents. Merchan’s immigration was humane.

Barring any unforeseen delays, the trial will begin on Monday. Trump is a veteran of many courtrooms as both defendant and witness, but this will be his first criminal trial. This will be a very different experience for him. Notably, Trump will not be able to breeze in and breeze out of the proceedings at will. Like the recently deceased and largely unlamented OJ Simpson, Trump will be required to be present at his criminal trial every single day.

The first order of business will be what is referred to as “voire dire,” a Latin term meaning “speak the truth.” In a legal context it refers to jury selection. To save time, Merchan will begin by implementing sweeping juror disqualifications. For example, prospective jurors will be excused if they are unable to attend every court session for religious reasons. He’ll want to excuse jurors who are regular consumers of, say, Fox News or MSNBC. Merchan will want to know if any have read certain books. For example, I would be immediately disallowed from serving on the jury because I read Michael Cohen’s books “Disloyal,” among many other things.

Merchan will instruct prospective jurors that Trump is charged with falsifying business records in order to unlawfully influence the 2016 presidential election. If called to serve, they will be expected, after hearing arguments from both sides, to render a judgement on those charges and hand down a verdict of guilty or not guilty.

Once twelve jurors and up to six alternate jurors are empanelled, the trial proper will begin with the prosecution presenting the people’s case. As with all criminal trials, it is the prosecution’s job to prove to the jury, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant is guilty of the specified charges. In this instance, 34 individual criminal counts of deliberately falsifying business records with the aim to unlawfully influence the 2016 presidential election. This is what is often referred to as the “prosecution’s burden.”

A word about the prosecution’s burden. Inside the courtroom, the defendant is to be presumed not guilty of the charges and will remain presumed not guilty until or unless the prosecution has successfully discharged its burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The defendant is not required to mount any answer to the prosecution’s charges, but they almost always do.

Note that the defendant is presumed “not guilty” as opposed to “innocent.” Innocence is not a feature of a criminal trial. No matter how many times Trump supporters might insist that we are, you and I are under no obligation to presume that Donald Trump is innocent, or more precisely not guilty, of the criminal charges brought against him. That is an injunction that exists exclusively for the jury inside the courtroom.

Once the prosecution has rested its case, it will be Trump’s turn, through his lawyers, to present his side. Because the case for guilt is heavily documented by written records and witness testimony, Trump will probably try to present any number of conspiracy theories in support of his belief that the charges and evidence are fake, and that his presence in the courtroom is purely “political.”

Trump might even take the position that, even if the charges are true, the jurors should disregard the charges and acquit him anyway because the law itself is unjust. This is a tactic referred to as “jury nullification.” It’s a dangerous, extralegal gambit because it is, in effect, a tacit admission of guilt and an attempt to override the law. Attempts at jury nullification could be disallowed by the judge if they are too blatantly pursued. Once Trump’s lawyers rest their case the prosecution will have a brief opportunity to rebut everything his lawyers said.

Throughout the course of the trial, witnesses will be called for both the defence and the prosecution. These witnesses will probably include (but are not limited to) Trump’s former lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen, Stormy Daniels, former Playboy model Karen McDougal, with whom Trump is alleged to have had a 10 month extramarital affair, former White House communications director Hope Hicks and former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker.

In evaluating this case in advance, we need to learn to differentiate between events where the past is a guide and events where the past is no guide. The mundane features of this case aside, there exists no precedent for the criminal prosecution of a former American president. In short, there is no certain outcome to this case. For example, it’s not even clear what the defendant will be personally referred to. There can be little doubt that he will be called “the president” or “mister president” by his lawyers. But what will members of the prosecution call him? I hope it’s nothing more deferential than “Mr Trump.”

There are a million variables to this case and, in the final analysis, no matter how much we may protest otherwise, the final word on the final outcome will be up to the jury. To be sure, I have every reason to hope that the prosecution’s case will be competently delivered and lacerating in its effect.

But the jury, and the jury alone, will decide the question of Trump’s guilt. And, if he’s found guilty, the judge, and the judge alone, will decide his punishment. We must have faith in the time-honoured institution that has, at last, brought Trump to the threshold of justice, and faith that justice will at last be delivered. And, as ever, ladies and gentlemen, brothers and sisters, comrades and friends, stay safe.

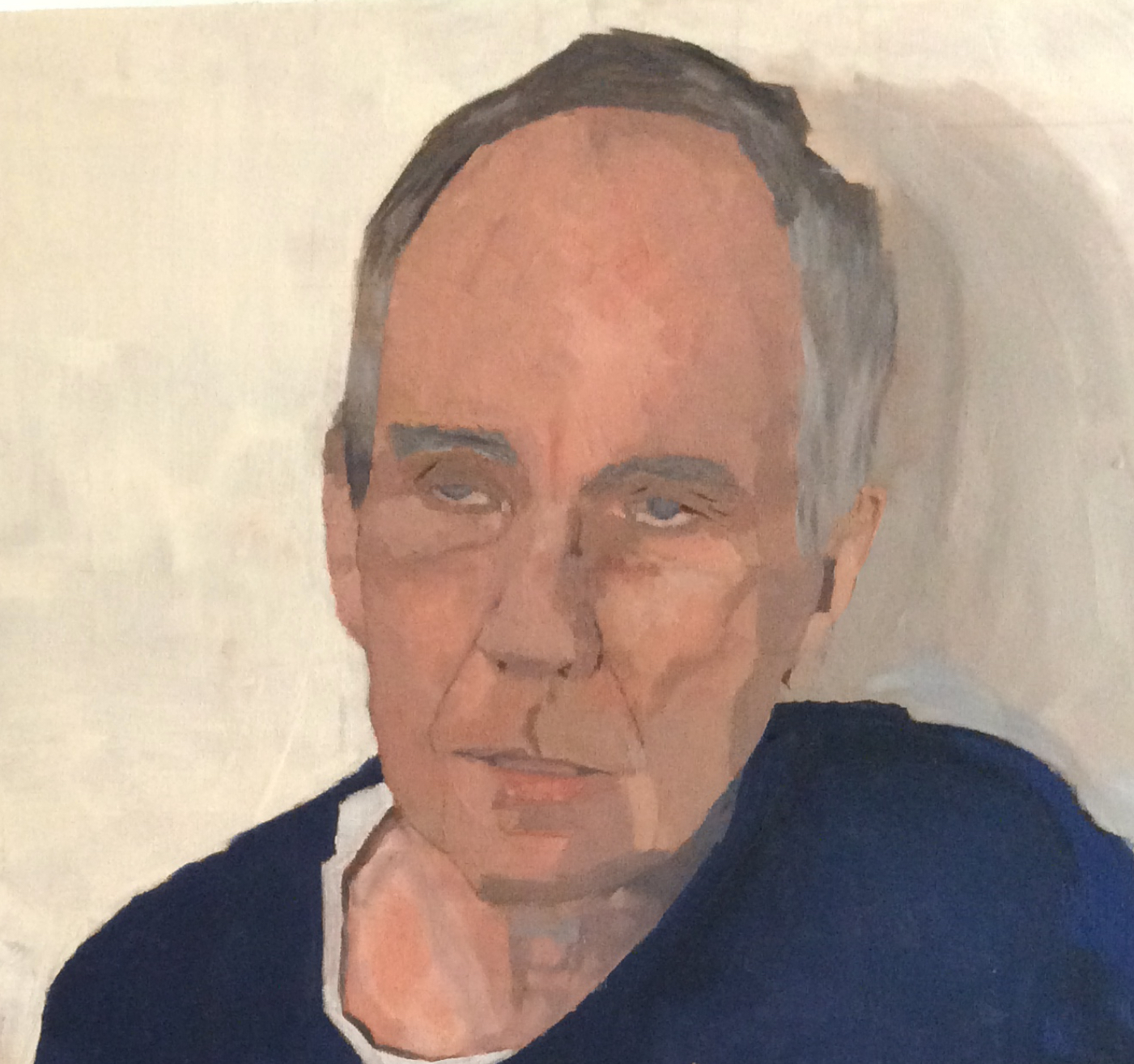

Robert Harrington is an American expat living in Britain. He is a portrait painter.