The difference between anecdotal and statistical evidence

Those of you already acquainted with the stark differences between anecdotal and statistical evidence — and why those differences are essential to the advancement of science and the understanding and pursuit of human truth — may want to skip this article. For the rest of you, welcome. I hope my small offering is both of use and comfort to you.

We have a job ahead of us, you and I. It is left to us to save the United States of America and the planet earth. What once sounded like a hokey premise for a bad superhero movie is now our lot in life. We are the last bastion against tyranny, and it’s our duty to acquire the necessary tools to secure that bastion. One important tool is understanding the difference between anecdotal and statistical evidence, and once understood, applying that understanding to bringing people over to our side.

Anecdotal evidence is personal experience, or the personal experience of a third party, applied inductively. Two examples: first, a friend had a bad experience with a particular car she recently bought, you therefore assume that car is a lemon. Second, you learn that people are reporting wonderful results from a particular diet, you excitedly decide to try that diet yourself.

Both examples can be true, that is, both reports from the friend and the group can be accurate, and yet both can be (and probably are) completely misleading. The friend’s car could be the most reliable and best built car on the road. She just got a bad one. The diet could be bad for your health and no more successful than any other diet, that is, the vast majority of people who start diets will fail, and this new diet is no exception.

However, a car that is statistically shown to be unreliable through rigorous scientific inquiry really is a lemon, (if there are such things as cars that are lemons any more.) Also, if a peer-reviewed diet subjected to a rigorous clinical trial with a control group is shown to be significantly more effective than most other diets and is also good for you, you can reasonably expect better results with that diet.

That ought to be all I have to say on the subject. Unfortunately, the problem with anecdotal evidence is it’s so attractive, and the problem with scientific statistical evidence is it’s so unattractive. We like to hear stories about personal successes and failures, while dry statistics seem boring, abstruse and hard to relate to. Moreover there’s also a sociological mistrust of statistics. Most people have heard of the book “How to Lie with Statistics” and assume, incorrectly, that it means statistics aren’t reliable.

As if all this isn’t confusing enough, relying on statistics seems to suggest that finding scientific truth is done by way of democracy. That is to say, the more votes you get the truer it is. That isn’t correct either.

For example, if large groups of people suddenly leave America to live in Canada, I wouldn’t necessarily attach too much significance to that. But I do attach a great deal of significance to the fact that Timothy Snyder, together with two other colleagues, recently quit Yale University to work at the University of Toronto. Dr Snyder is a leading expert on the Soviet Union and the Holocaust. He is leaving because he sees patterns developing in American politics that he doesn’t like.

Dr Snyder’s anecdotal evidence is worth a hundred statistical examples of Americans leaving for Canada. So statistics aren’t necessarily the be all and end all. In the midst of all this we have to remember that some opinions are far more important than others. To fail to recognise that is also dangerous.

For example, millions of Americans believe that the Covid pandemic was a hoax. They rely on the uninformed opinions of politicians to confirm this nonsense. Yet they revile and repudiate Dr Anthony Fauci, a man of remarkable qualifications and trustworthy opinions. The truth is that Dr Fauci is reliable not only because of his vast experience and personal eminence but also because scientific studies and peer-reviewed clinical trials back him up.

In short, clinical trials and people who know what they’re talking (if you’ll pardon the word) trump anecdotal evidence espoused by politicians on behalf of an agenda. That ought to be obvious. But millions of people don’t understand why it is obvious. It’s our job to help them understand.

Lastly, anecdotal evidence can make us intolerant, as in, “I have no trouble keeping slim, what’s your excuse, fatso?” We have to be careful before judging people too harshly. Sometimes we can’t always understand what has made them the way they are. We can’t always know that we wouldn’t be exactly where they are given their circumstances, exposing our supposed superior wisdom or morality as nothing more than random chance.

It is sometimes said that we are lucky in that the forces arrayed against us are incompetent. But I submit to you that the reason they are incompetent is because they lack our insight into how the world works. In other words, if they saw things more clearly they wouldn’t necessarily be more efficient in their pursuit of evil, they would be on our side. It’s our job to help them acquire the insight that is much easier for us. And helping people understand the difference between anecdotal and statistical evidence is a step in that direction.

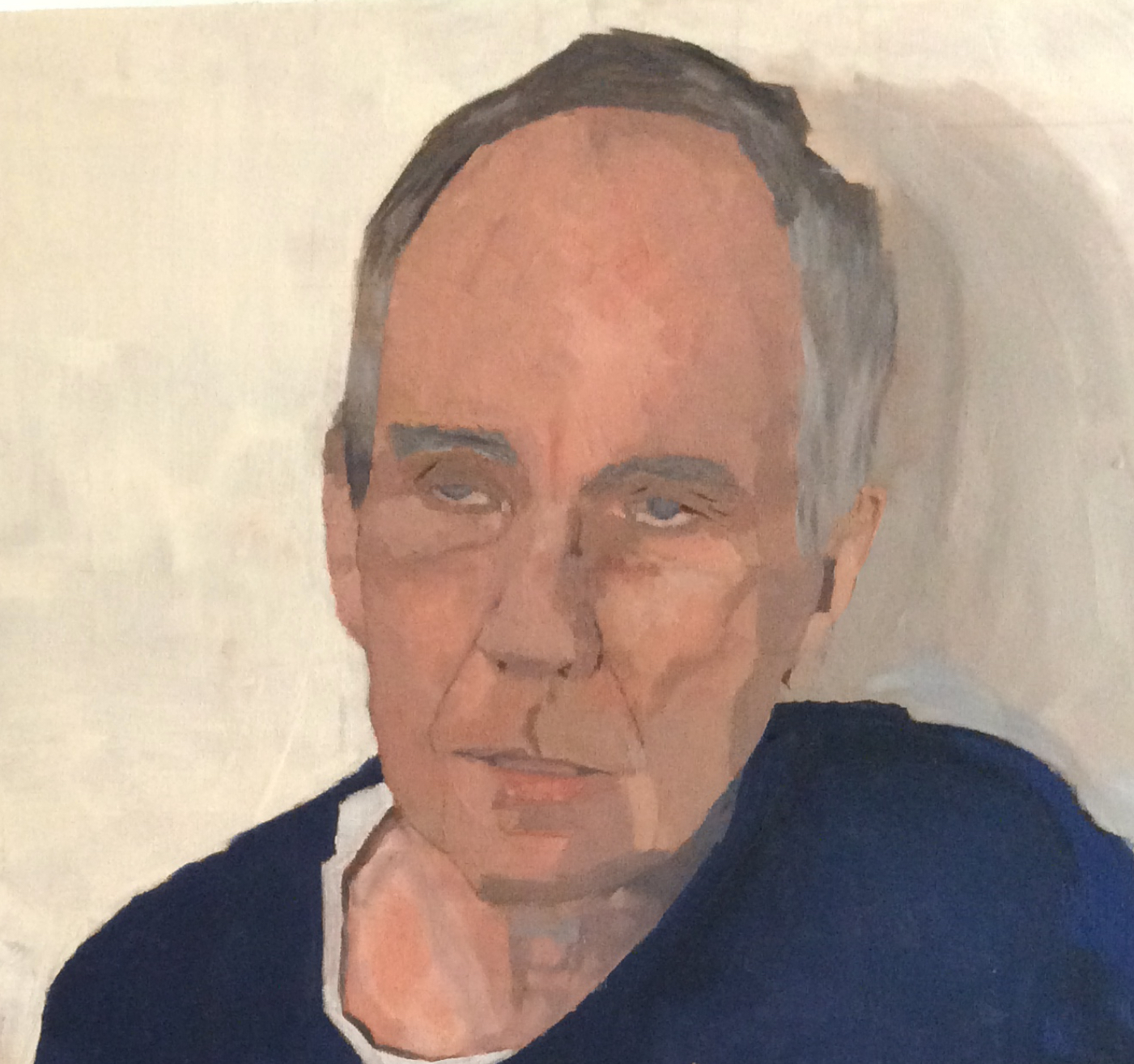

Robert Harrington is an American expat living in Britain. He is a portrait painter.