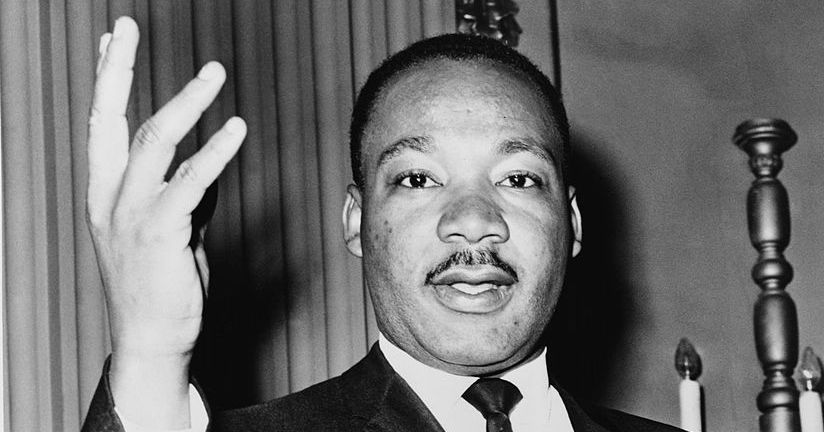

Reflections on Martin Luther King

Today (as I write this) is Sunday, 15 January, 2023, Dr. Martin Luther King’s actual birthday. Had he not been murdered by an inadequate racist nonentity, Dr King would today be the remarkable (but not unheard of) age of 94. I don’t know what kind of world it would be today had we not been robbed of nearly 55 years of his magnificent voice, but I have no doubt it would be a better one.

Dr. King’s legacy cannot be adequately summarised by my feeble words in this short space. I’m here merely to remind you of it. I would never presume to do anything approaching adequate justice to his incomparable memory.

Of course, no remembrance of Dr. King would be complete without reverent mention of his “I have a dream” speech, which is justly regarded as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory. I defy anyone to read it today without tears in their eyes. Indeed, I would question the humanity of the man or woman who can read King’s words wholly dry-eyed by the contrasting light of today’s tumultuous and racist political landscape.

The speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial 28 August, 1963, less than a mile from the Kennedy White House, is made all the more remarkable in that its most famous part, the eponymous “I have a dream” passage, was largely extemporaneous. Dr. King departed from his prepared speech, possibly at the prompting of Mahalia Jackson, who shouted from behind him, “Tell them about the dream!” And tell us about the dream he did.

Here is one of the memorable passages of that speech: “I have a dream — that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” Dr. King dared to hope — dared to dream — that his children would grow up in a world where they would “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Martin Luther King had almost five years to live after that speech, but it’s too often treated as the last thing he said, the last thing he did. What he did after was equally important. He brought the civil rights movement to its pinnacle of effective maturity. We can measure the power of that final legacy in part by the degree to which America’s most virulently racist party, the MAGA Republicans, today sometimes attempt to disingenuously co-opt him.

But when I think of him, our brother Martin, I am reminded of the signs he inspired, held by striking sanitation workers in Memphis, his final stopover before he belonged to the ages. “I am a man,” the signs said, simply. It was a powerful proclamation that has echoed down to us and taken shape again in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement. The racist attempt at refutation then, that “we are all men,” is mocked today in the hollow and obtuse observation that “all lives matter.” The final point, so often missed, was that none of us are men (or women) until all of us are. And no lives matter until all of them do. We can never be free at last until all of us are.

The night before he was murdered, Dr. King delivered a remarkable speech encouraging the on-strike sanitation workers of Memphis with stirring words of resolution. Toward the end of the speech he abruptly changed gears and became eerily reflective, even philosophical, about his own mortality. And then he said, “I have been to the mountaintop … and I have seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land.” It was a chilling moment. He died the next day.

I am privileged to be old enough that my life intersects with his — barely. I didn’t understand then until much later why we are reminded of his human flaws with almost obligatory, insistent regularity. I will venture to say that at least one writer would have mentioned them in the comment field below (and still might) were it not for the words of this paragraph. But the impulse to remind everyone that MLK was a human being comes from the deep wells of resentment. Many of us still can’t entirely permit a black man to be a great man.

Well I, for one, am glad he was human. Our great people today are men and women of flesh and blood, not cardboard false gods like the ones created by the MAGA right. We don’t need a bloated, red-hatted spewer of slogans and hate. We are not a cult. We are a movement. And Martin Luther King was one of the greatest exponents of that movement, and it’s why we will honour his memory with another national observance of his birthday tomorrow. Martin Luther King was a man of peace, not hate, and we honour him best when we choose to imitate his peace. And, as ever, ladies and gentlemen, brothers and sisters, comrades and friends, stay safe.

Robert Harrington is an American expat living in Britain. He is a portrait painter.