How Donald Trump cheated

On August 13, 2017, BBC Stories posted a tweet, captioned “Meet the woman who wrote Donald Trump’s campaign Facebook posts – and the tech firm that helped him get elected.” Attached to the tweet was a video in which a very friendly and talkative woman named Theresa Hong shows a BBC reporter around the former headquarters of the digital arm of Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign in San Antonio, Texas. This short video presents the gist of a longer BBC Two documentary, entitled “Secrets Of Silicone Valley, Series 1, The Persuasion Machine.”

“This was our Project Alamo,” Hong says as she and the reporter enter the building, and then she explains that the project’s name was originally based on the data set provided by Cambridge Analytica – a company specializing in psychographics – and later became the name of the digital campaign operation as a whole. Hong points to various areas of a now empty office suite and helpfully indicates who was sitting where in the campaign’s former data center.

“Cambridge Analytica was here,” she says and then reveals that representatives of Facebook, Google and YouTube were also present and working on site as “hands-on partners”, making sure that all the needs of the campaign that was pumping millions of dollars into those companies were being met. The common goal everyone was working on was to utilize social media platforms as effectively as possible.

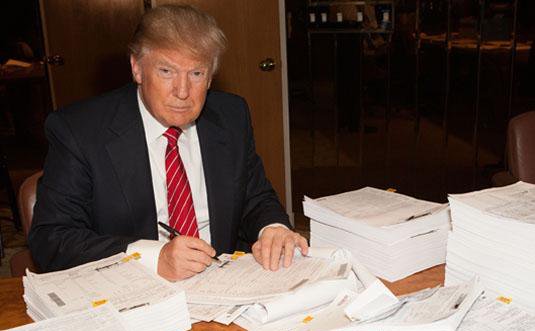

While Donald Trump managed his Twitter account all by himself, Theresa Hong was one of the people tasked with composing some of his Facebook posts, channeling the candidate’s voice with a lot of “believe me’s”, “also’s” and “very’s.” The ads produced on the computers of Project Alamo – often at a rate of a hundred posts a day – were then infused into the bloodstream of the internet in various different renditions, tailor-made and targeted at specific audiences, or, in Cambridge Analytica’s lingo: audience “universes.”

How did this technique that has become known as micro-targeting work? How did the Cambridge Analytica people know which style of ad would work on a particular type of person? – “That’s their secret sauce,” Theresa Hong says.

As we learned in the context of the 2018 Facebook data scandal, the main ingredient of that secret sauce appears to have been the Facebook data of an estimated 200 million American users, largely harvested without either the knowledge or the consent of said users.

“Without Facebook, we wouldn’t have won,” the friendly and talkative campaign staffer states at the end of the video. Whether this statement in its absoluteness is true or false is a question that will never be fully answered. However, what has emerged from the ongoing debate surrounding Project Alamo, Cambridge Analytica and Facebook is the realization that social media has become an important battleground in the context of political campaigns. The name “Project Alamo,” with all its ominous connotations of a fierce battle, is more than apt in this sense.